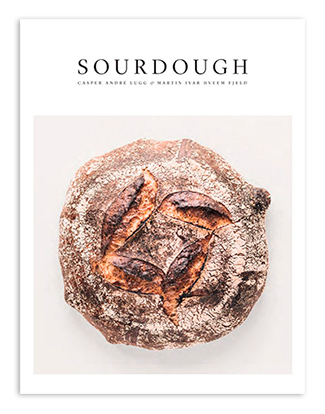

Sourdough, Heritage Grains, and a New Book

You may not have heard their names, but I bet you have seen the Norwegian sourdough baking duo’s Instagram account: Casper Andre Lugg and Martin Ivar Hveem Fjeld run @illebrod, through which, in the past six years, they have inspired over 30,000 followers to improve in the craft of bread making.

Now, in the form of their bread-making book, Sourdough, which was published in the UK last year, they are bringing their lessons to the international bread making community.

As a long time follower, I have been impressed by the way Casper and Martin combine heritage grains, high hydration, and long fermentation times to make sourdough bread with a deliciously open crumb — even at rather high percentages of wholegrain flour.

I was excited to ask a few questions about bread, baking and the new book! Here’s what Martin told me.

**

The Making of Two Bakers

Jarkko: Tell us a bit about yourself — how did you get started with bread making and what has kept you hooked since then?

Martin: I started baking sourdough bread about five years ago, after being introduced to it by Casper. He had just discovered this magical bread formula, and insisted on me trying as well — he couldn’t recommend it enough. So I got my first starter from him, baked my first sourdough loaf, and it was a complete disaster.

It looked more like a cannonball than a loaf of bread, and I went back to making simple yeast rolls and stuff, which I had been doing for a while.

But Casper wouldn’t let it go. So, I tried again, and this time it worked. It didn’t take more than those first OK results to get me hooked. It was like discovering what bread really was, and there was no returning to industry bread or even my yeast rolls after that.

Jarkko: Bread has been a shared project between you and Casper since then: first on the Instagram profile and now also your new book. Can you tell a bit about your collaboration?

Martin: Casper and I have been working very closely from the beginning, and still today talk about bread on the phone almost every day — sharing ideas and thoughts and experimenting as a team.

Casper had been baking for some months before I got into it, and then we started the Instagram account together about a year after that, I think. The book project was very much a continuous team effort: we wrote more or less everything together via Skype, and we both met up with the photographer for each photo baking session, baked all the breads together, to the point were we actually slashed half of the scoring on all the loaves…

Local flour sourdough bread by Illebrød, from their Instagram feed

Today, we follow each other’s work very closely as well. But our baking situations are quite different now. Casper is primarily a home baker, with small batches to supply his family, first and foremost.

For me, it has become my day job.Ille Brød is now a bakery as well — located in the center of Oslo. I’m very excited about it! This means that I’m baking larger batches and having to think a little differently about the process.

But we still work as a duo and regularly share thoughts on how things can be done differently, come up with new recipes together and just talk bread all the time. Neither of us, I think, could imagine a life without baking bread at this point.

Jarkko: Where does the name, Ille Brød, come from? According to Google Translate, “ille brød” means “bad bread”…

Martin: Haha, yes, that’s the literal translation.

But in our Norwegian dialect, “ille” is used in another sense as well, meaning “very” or “really”, and usually when speaking of something that’s good, turning it slightly askew — as in “awfully good.” So it’s more like “very bread”, if that makes any more sense…

We started saying ille brød to each other as a half joke, and when we used it as the name for our Instagram account, it sort of just stuck to us.

Jarkko: How would you describe the role Instagram, and the bread making community there, have played in your bread making journey?

Martin: Instagram has been very important for us, for inspiration, making contacts and friends, and of course for sharing and getting feedback. It’s such a great baking community that has formed there, we’re very thankful to be a part of it.

A Book on Sourdough Bread

Jarkko: Your book, Sourdough, which was originally published in Norwegian in 2015 is now available also in English. We love books and everything about them, so can you tell a bit about how the book deals came to be?Looking back at your Instagram posts from the time, one can see that a global release was at least a dream of yoursalready then…

Martin: We were really lucky with both the Norwegian and English book deals.

Literally the first publisher we called about the book — actually just to ask about some deadlines, not even trying to sell the concept — immediately got excited about the idea, and we’ve had that same editor who answered the phone ever since.

Then, the publishing house brought one copy of the book to the Frankfurt book fair. There, when one of the editors at Modern Books/Elwin Street visited their stand, the book caught his eye, and a deal was made from there. We’re very happy about getting published in English — and now even in French!

That was definitely a dream from the start.

Jarkko: In a world where there are so many bread making books already, what’s the ‘thing’ yours adds to the whole? What aspect in it makes you the most proud?

Martin: The main outline of this style of baking is inspired by others of course, such as Chad Robertson’s approach, but there are some differences in our method that we think are key to getting the loaves we want.

We learned this craft from other bakers, just like everyone else, and then tried to take it a step further. And we’re still working to improve every day. It never ends, thankfully — that’s what makes it fun.

But what makes us most proud about the book is perhaps the focus on ancient and heritage grains, a field which still deserves much more attention from bakers. The book is kind of divided into two main themes: the method on one hand and introductions to the rich variety of grains on the other.

Things That Matter in Bread

Jarkko: You care a lot about grain: local, ancient, heritage, whole grains… all are mentioned again and again in your Instagram posts. Why do the grains we use in bread matter?

Martin: Taste, sustainability and baking quality are the main factors for us when choosing flour. The three don’t always appear together, so you have to have some guiding principles.

Early on, we felt that we had the choice between stronger (often industrial and roller milled) flour that produces very expansive and impressive breads and weaker flour from stone mills using old grain varieties that are often harder to work with — but so much more flavorful and more sustainable both in terms of health, the environment and biodiversity.

It would seem like a no brainer when you put it like that, but for a baker, just as for a cook, appearance is important.

So, we never took an extreme position, but rather worked on improving the techniques so that we could use as much as possible of the weaker but (by all other measures) better flour, without having to compromise much on volume and spring. Today, we only use stone milled organic flour in all our breads, from grains that are grown and milled just a couple of kilometers away. And when baking quality allows it, we stick to ancient and heritage/landrace grains for the sifted part as well. Which is most of the time: we haven’t used anything else at the bakery so far!

Another important reason for us to use this flour is supporting small scale farmers and millers who are working uphill in a very industry-dominated world, competing with big money. It might not be the most available flour, you might not find it in the supermarket, but in our opinion, it’s definitely worth seeking out.

Jarkko: How about sourdough? What is it about it that captivates your imagination?

Martin: To me, the most captivating and awe-inspiring thing about baking with sourdough is that it’s entirely natural, in the sense that nature has provided us very directly with everything we need to bake this amazing bread.

The ancient grain varieties first evolved in the wild, the bacteria and yeast spores were always present, ready to feed on the sugars — we just had to crush the grain, mix in water and let it sit. That’s how the first sourdough baker did it 5,000-6,000 years ago. It’s the same to today, and it will always be available, even without modern industry.

You can’t say the same for bread made with commercial yeast.

We’re not fanatical yeast haters, but it doesn’t have the same depth and magic about it. And it certainly can’t match the smell and taste of real sourdough bread made with freshly stone milled flour!

Jarkko: Finally, with your book now out there for the whole world, what’s next for you in the world of bread?

Martin: Opening the new bakery will take up a lot of time. I’ll do some more courses, and maybe go back to England this summer to do a course in London — it’s great to meet other passionate sourdough bakers from all over, sharing thoughts and approaches.

Otherwise, we’ll just keep baking bread everyday. Eventually we might do some more writing.

Martin’s Tips For Great Bread

Feed your starter regularly. Preferably, keep it at room temperature and feed it once or even twice a day. Don’t use it too early to make a leaven. If you feed with rye and wheat (as we suggest in the book), it might have a long cycle, so let it sink a little after its final peak before using it, just to be sure.

Keep the room warm during bulk. In our opinion, it’s better to over proof a little than ending up with an under-fermented loaf, so try pushing your boundaries for hydration and fermentation.

And use the best flour you can find, freshly stone milled and local — if you can get a hold of it.